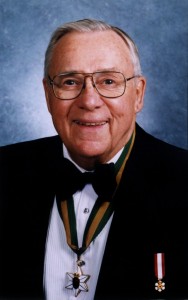

DOB: 1925

DOB: 1925

Address: 837 King Street (1968-1988)

Back home in Canada after two years at Britain’s Oxford University, young Allan Blakeney knew there was no place he’d rather be than Regina.

“I wanted to see what the (Tommy) Douglas government, which was then a pioneering government, might be doing in Saskatchewan,” he recalls. “I wouldn’t have gone to work for any other provincial government.”

But at the time, Douglas’ Co-operative Commonwealth Federation government had no place for Blakeney. His application for a job – any job – was turned down, and he headed for Edmonton and a private law firm instead. But four months later, in spring 1950, Blakeney’s luck changed: a position opened up as legal adviser to Saskatchewan’s Crown corporations. He pounced on the opportunity.

Though he’d intended to stay only a couple years, long enough to “get a feel” for CCF government, Blakeney remained a civil servant until 1958. Then, with an eye toward running in the 1960 election, and preferring not to run as a government employee, he returned to practising private law.

Blakeney earned his seat during an election that “was fought on medicare, and little else,” as he puts it. The CCF was returned to power, and he was quickly appointed Minister of Education, then shuffled into a new post as the provincial treasurer. As the debate over medicare heated up, Blakeney was heavily involved in introducing free health care despite public protests and a determined doctors’ strike.

But the controversy over medicare took its toll on the CCF’s popularity, and the party was defeated in 1964. After a second defeat in 1967, party leader Woodrow Lloyd stepped down, and after a hotly-contested leadership convention Blakeney emerged to take his place. Under Blakeney, the CCF – now renamed the New Democratic Party – swept into office in 1971 with more seats than it had won since 1944.

As Blakeney was leading his party back to the governing side of the legislative building, he also led his family into a much humbler part of Regina. In 1968, they had a house built at 837 King Street, in the heart of Blakeney’s riding, and moved there from Lakeview.

“I said ‘If I’m gonna represent those people, I think I should live there,” says Blakeney.

The move, he recalls, took him out of familiar middle-class surroundings, and into a solidly blue-collar neighbourhood that broadened the soon-to-be-premier’s horizons.

“When I was in North Central I met with a lot of people who were straight working stiffs, had never been to university and never really expected their kids to go to university, which was sharply different from my own life,” he said. “I didn’t have a lot of working class experience, and I got a little of that in North Central.”

Over his 11 years as premier, many of Blakeney’s greatest achievements championed the working-class Saskatchewanians he lived alongside. His government put through legislation to improve the workers’ compensation system and raise minimum wages to among the highest in Canada, as well as adding prescription drug benefits and childrens’ dental care to the universal health services provided by the province. Blakeney also takes pride in his success putting resources like potash and uranium under public control, and his efforts to encourage a common feeling of pride and connection amongst the province’s citizens – what he calls “a sense of Saskatchewan.”

Always faced with a heavy political workload, Blakeney admits he couldn’t spend nearly as much time as he wanted to with his constituents in North Central. But he recruited a team of a locals to keep an eye on the neighbourhood in his absence, helping him head off trouble before it became serious.

North Central’s Native population rose sharply during Blakeney’s time as premier, and though he says most residents “had no great difficulty getting along with them,” matters of inter-racial tension sometimes demanded his attention. So he made a point of working with the neighbourhood’s Native leaders, who helped him bridge the racial divide. That connection later helped him make the most of provincial low-income housing projects, by subletting the buildings to Native groups who were in close touch with those in need of housing. Living in North Central also helped him realize the difficulty of adapting from reserve to urban life, and in in the mid-70s he assigned a permanent social worker to each of the neighbourhood’s elementary schools, to help students and staff cope with those challenges.

Blakeney’s political fortunes worsened suddenly in 1982, as the NDP suffered a staggering defeat that reduced them from 44 seats to nine. He stayed on as party leader, and by 1986 the NDP had rallied enough to win 28 seats and the largest share of the popular vote. But it was not enough to reclaim government, and a year later Blakeney decided it was time to resign from politics. In 1988 — 20 years after moving into the neighbourhood – he left Regina to begin teaching law, first in Toronto and then, from 1990 onward, at the University of Saskatchewan.

In his retirement, Blakeney joined a Canadian delegation to the post-apartheid South Africa, helping the newly-democratic country design a system of government that would accommodate its wide ethnic diversity. It was a challenge that Blakeney felt well prepared for, after his years governing a province as diverse as Saskatchewan.

After his work in South Africa, Blakeney returned home to Saskatoon. Though he still teaches occasional law classes, he maintains he hasn’t “done anything very lively” since then.