DOB: 1923

DOB: 1923

Address: 7-block Robinson, 1927 – 1942 (approx)

Schools: Kitchener, Scott

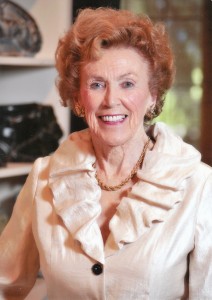

Jacqui Shumiatcher (born Jacqui Clay) has always believed in sharing the wealth. It’s something she learned as a child, growing up in Regina’s North Central neighbourhood.

“As far as giving, my mom said that if I had a toy or two toys, and somebody didn’t have any, I’d give them the toy,” she explains. “And same with candies: if I had candies I’d give the candies to everybody, and I wouldn’t have any left for myself.”

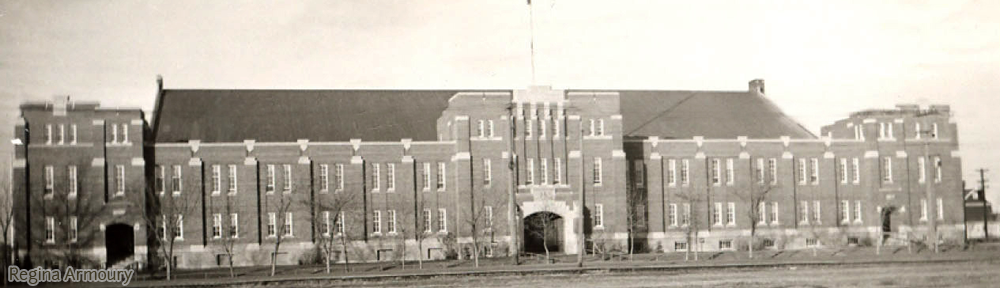

She didn’t often have much to give away, though. Jacqui moved from France to Regina with her mother and brother in 1927, when she was not quite four years old, to join up with her father. Though he’d come to Regina to live near an old army friend, “why he picked (what’s now the North Central) area, we’ll never know,” says Jacqui. Instead of the brick houses and stone roads of France, her family found themselves in a neighbourhood that featured dirt roads, wooden sidewalks, and a promise from the city that their home on seven-block Robinson would never have running water—a problem her father solved by rigging up a system to collect rainwater from their roof and pump it into the house.

It was a far from wealthy area, and the Clays were a far from wealthy family. But though they grew up without a telephone or car, and saved everything from paper to rubber bands because they never knew when they might get more, they never felt poor.

“We may have been classified as underprivileged by some, but we never thought of ourselves in that way,” says Jacqui. “We were happy with what we had.”

Much of that happiness came from the love and support her family gave one another. It was a bond strong enough, says Jacqui, to make life enjoyable despite belonging in a low-income family and neighbourhood.

“Because we had the love of our parents and we were closely-knit, we didn’t fight, and we didn’t do any of those things,” she says. “That gave us security.”

“I think where you’re brought up doesn’t matter … the family unit – that’s the important thing … as long as you have that family love, then it doesn’t matter where you live.”

True to her words, Jacqui had no trouble keeping herself entertained as she grew up in North Central. She filled her time playing ball with her brother in a nearby field, or pretending to drive an abandoned car that sat in an empty lot near her house. Plenty of her time was also taken up by school, which included Saturday morning classes. Her elementary school, Kitchener, had fountain pens, inkwells on the desks, and strict rules—students were strapped for making mistakes in math or spelling. Scott, her high school, was less strict. Jacqui fondly remembers a passionate French teacher there who helped her learn her ancestral language, (which Jacqui now speaks fluently) by importing magazines and records from France at her own expense.

In 1940, Jacqui got her first job: teaching shorthand and typing at the Scared Heart Academy on 13th Avenue for $1 a day (minus the cost of the instruction books, which she had to pay for herself.) She later moved to the audit department of the Simpsons department store, and then, in 1942, took a job checking weather instruments and relaying messages at the airport. The position required her to work eight-hour solo shifts, sometimes back-to-back, doing work so time-sensitive she couldn’t even take bathroom breaks.

While Jacqui was working at the airport, her father and brother left to serve in the Second World War. The family sold their house on Robinson Street, and Jacqui moved with her mother to a downtown apartment. Working night shifts at the airport while living in a place too noisy and hot to sleep during the day wore on her, and—despite the anger of the Department of National Defence, which considered the airport work part of the war effort—she soon took a new job at a mortgage company. But that job didn’t suit her either: she disliked work that involved foreclosing on the homes and land of the poor. So she soon switched over to a position at the Canadian International Bank of Commerce, and eventually returned to her old high school as the principal’s executive secretary, continuing to ignore the way that job-hopping was frowned on at the time.

“In those days … if anybody had that kind of movement around, employers might suspect there was something wrong with them, because they couldn’t hold a job,” she says. But her employment history didn’t stop her from landing the job that would shape the rest of her life. In 1947, responding to an ad in the Leader-Post, she biked over to the Legislative Building for an interview, and soon found herself working for Morris Shumiatcher, a legal adviser to Premier Tommy Douglas.

She eventually left the job at the Legislature, but stayed connected to Morris, looking after matters for him while he was away from Regina and helping establish his law firm once he returned to the city. The two were married in 1955, and Jacqui founded her own managerial company, which supported her husband’s law firm.

But it was their huge generosity as philanthropists and patrons of the arts, not their professional work, that turned the couple into well-known and much-loved figures in Regina. Regina’s symphony orchestra, the Globe and Regina Little Theatres, the Mackenzie Art Gallery, the University of Regina’s theatre and music departments—the list of institutions, and smaller projects, aided by the couple’s funding and leadership could go on for pages. So could the list of awards and honours that have been bestowed on them for their work.

Jacqui, who has remained the champion of Regina’s arts community since Morris’ death in 2004, is dismissive of the accolades her philanthropy has earned her. She says he’s just continuing the habit of sharing that she learned growing up in North Central decades ago.

“I’ve never considered myself a philanthropist. A lot of times it’s just automatic: I see something, I want to help. The only thing is I wish I were a multi-millionaire, because then I could help a lot more,” she says. But no matter how little or how much she’s able to donate, she plans to keep on supporting—and devotedly attending—arts activities and other events in Regina.

“I’m not an artist, and I’m not a musician, I’m not any of these things—but I can appreciate,” she says. “I think that’s probably why I’m living on, because I get so much joy from other people’s work and achievements.”